By Brenna Doheny, Marine Biomedicine and Environmental Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina

Allergies. Asthma. Type I Diabetes. Autism. Obesity.

Post-industrial societies are plagued with a rising incidence of these non-infectious diseases of mysterious origins, and children seem to be particularly hard-hit. While doctors seek treatments for an ever-increasing patient load, scientists seek the root of the problem. What could possibly trigger the increase in such seemingly disparate diseases?

Duke University neuroimmunologist Staci Bilbo suggests that the answer is not what’s new in the modern world, but what’s missing.

Specifically: worms.

Bilbo and a growing number of researchers are promoting the theory of biome depletion, also known as the “Old Friends” hypothesis. Humans coevolved with all manner of microbes and parasites, both around and within their bodies, which were in turn kept in check by the human immune system.

“There’s this idea that we’ve been leaning into this strong wind of resistance for our entire history on earth,” says Bilbo. “And now we remove it, and we’re falling off the cliff.”

At the heart of the biome depletion theory is the concept that the immune response to large, extracellular threats like worms balances out the response to intracellular threats like bacteria and viruses.

However, modern medicine and sanitation practices have radically changed the composition of the human microbiome, in most cases completely wiping out a very important constituent: parasitic helminth worms.

Remove helminths, says the biome depletion hypothesis, and an imbalanced immune system begins attacking the body’s own cells.

Now, Bilbo’s research on the role of the immune system in brain development brings a new dimension to the biome depletion theory.

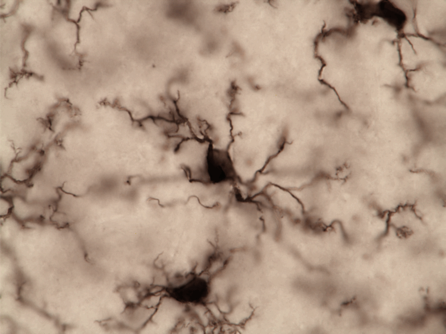

It all started when, as a graduate student, she first heard about microglia, immune cells that reside in the brain.

“I figured, they must be up there for a reason,” Bilbo says, “And, if they are immune cells, then maybe they have some kind of memory.”

Many cells associated with the immune response have memory: the whole concept of vaccinations is built on this property. Exposure to a small amount of an inactivated pathogen primes the immune system to mount a much larger response the next time it encounters this threat.

Bilbo set out to determine whether microglia also undergo some kind of priming during development, and if so, what implications this might have on adult brain function.

To test this idea, she exposed young rat pups to a mild strain of E. coli bacteria, which increased immune response and levels of stress hormones. When these exposed rats reached adulthood, they demonstrated an overactive immune response to a second bacterial infection, indicating an immune system sensitization.

Moreover, the exposed rats also experienced neurological changes, including decreased learning and memory, social interactions, and stress response. These behavioral changes were associated with changes in the structure and function of the microglia.

In short, immune system stress during early development caused profound, long-lasting changes in the brain.

To Bilbo, the implication is clear: “If we change microglial function specifically, then we change the way the brain functions.”

Bilbo’s research isn’t the first to implicate microglia in brain function. Microglia are involved in a process known as activity-dependent synaptic refinement. Babies are born with many more synapses than are needed, and over the first few years of life, the synapses that are used the most frequently are strengthened, while less active synapses are pruned away.

“Microglia have been shown to have a critical role in this – they actually go in and eat the ones that you don’t need,” Bilbo says.

Activity-dependent synaptic refinement is critical for normal brain function. In fact, aberrant synaptic pruning has been associated with autism.

So, how can a concerned pregnant mom protect her baby’s developing brain? Bilbo turned to the biome depletion theory for an answer.

She repeated her early immune system challenge experiment with one critical difference: prior to mating, half of the female rats in the experiment were infected with tapeworms.

When the pups were challenged with an E. coli infection, those whose mothers were infected with worms did not show an elevated immune response in the brain.

At weaning, the pups from worm-infected mothers were given their own dose of tapeworms. Once they reached adulthood, they did not display the immune system sensitization, cognitive impairment and behavioral changes typically seen in rats exposed to an early immune system stressor.

Most importantly, there were no changes in microglia structure.

“We still don’t know, is it mom having [worms] that’s critical, or do you need your own, or do you need both? We’ll have to figure all of that out,” Bilbo says. But she is very excited about the results of this first study, and its therapeutic implications.

So will doctors soon advise pregnant moms to slurp some worms with their prenatal vitamins?

Bilbo sees a long road ahead before helminth therapy becomes a reality. Currently, therapeutic helminths are illegal in the US, and the FDA has already classified them as a drug, “which is slightly ridiculous, in that they are organisms,” she notes.

Companies in the UK and Mexico are actively working on developing therapeutic helminths, however, and Bilbo’s colleague William Parker at Duke has investigated the types safest for use in humans.

One viable candidate is the very tapeworm Bilbo used in her rat experiments. Humans are not the normal host for this worm, so they cannot reproduce, and die off in just a few months.

“So there’s no way they can result in that horrific, nightmare scenario I think we all have in our heads of the worms taking over, and suddenly you’re just being eaten alive by worms,” Bilbo laughs.

Of course, the thought of ingesting worms is bound to make some patients squirm. Proper marketing would be key for altering these perceptions. Bilbo sees a promising example in the rising popularity of probiotics. “They don’t call it a ‘tub full of bugs,’ even though that’s what it is,” she says.

Bilbo is not at all squeamish about giving helminth therapy a try herself.

“I think the data in humans is so compelling that I would absolutely be up for it,” she says.

Bilbo presented the results of this research at the 2014 annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in Austin, Texas.

Brenna Doheny is interested in reproductive and developmental endocrinology in vertebrates, particularly how early developmental events, such as exposure to environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals, can affect the reproductive system.